Imagine a world where doctors couldn’t see inside your body without cutting you open. Where a broken bone required invasive surgery just to diagnose. Where tumors remained hidden until it was too late. This was reality until November 8, 1895, when physicist Wilhelm Conrad Röntgen became the first person to observe X-rays, an accidental discovery that would transform medicine, physics, and our understanding of the invisible world around us.

Within weeks of his announcement, X-rays were being used in hospitals worldwide. Within a year of Rontgens announcement, the application of X-rays to diagnosis and therapy was an established part of the medical profession. This wasn’t just a scientific breakthrough—it was an instant revolution that continues to save millions of lives today.

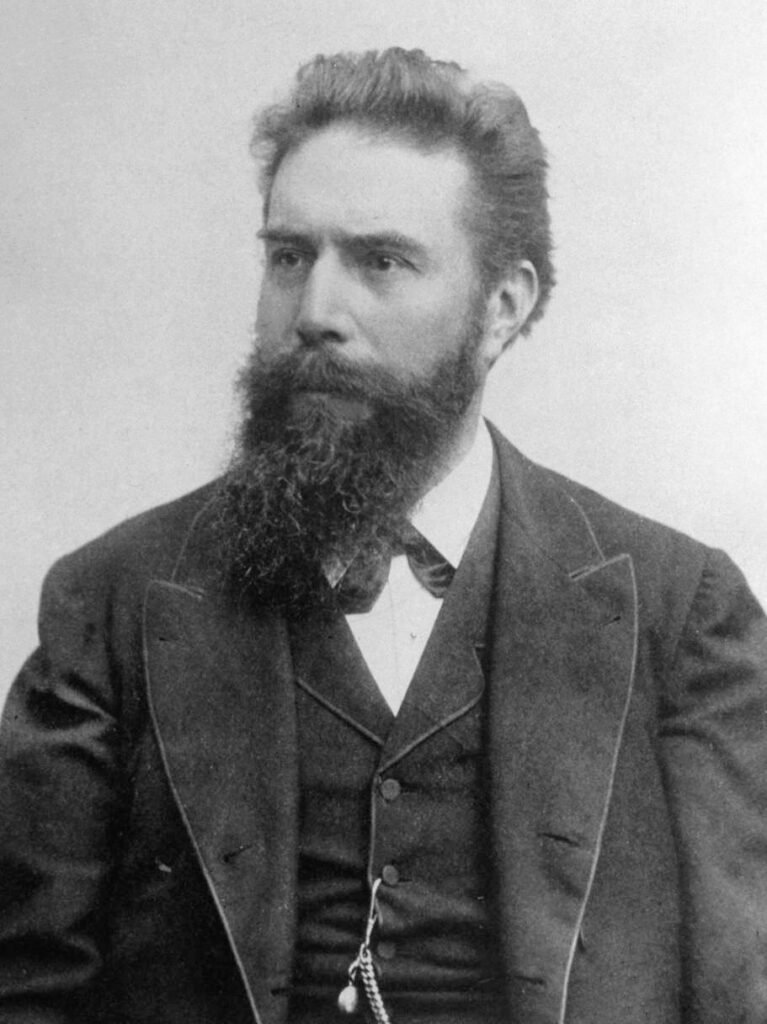

The Man Behind the Miracle: Wilhelm Conrad Röntgen

Wilhelm Conrad Röntgen was born on March 27, 1845, in Lennep (now part of Remscheid), Prussia, into a merchant family. His path to scientific glory was far from smooth. As a student in Holland, he was expelled from the Utrecht Technical School for a prank committed by another student, an unfair punishment that initially prevented him from obtaining academic positions despite his brilliance.

Despite these setbacks, Röntgen persevered, eventually earning his doctorate and becoming a respected experimental physicist. By 1895, he was a Professor at the University of Würzburg in Germany, conducting experiments that would accidentally change the world.

A Scientist of Integrity

Rontgens character was as remarkable as his discovery. He remained modest and never tried to patent his discovery, believing that scientific knowledge should benefit all humanity. This selfless decision allowed X-ray technology to spread rapidly worldwide, saving countless lives that might have been lost if the technology had been restricted by patents.

The Fateful Night: November 8, 1895

The Experimental Setup

Röntgen was investigating the external effects of passing an electric discharge through various types of vacuum tube equipment, specifically working with what’s known as a Crookes tube—a glass vessel with positive and negative electrodes used to study cathode rays.

In the late afternoon of November 8, 1895, he carefully constructed a black cardboard covering and covered the Crookes-Hittorf tube with the cardboard, attaching electrodes to an induction coil to generate an electrostatic charge. He darkened his laboratory to test whether his cardboard covering was truly light-tight.

The Moment of Discovery

As he passed the induction coil charge through the tube, he noticed a faint shimmering from a bench a few feet away from the tube. This glow was coming from a barium platinocyanide screen he had been planning to use next in his experiment.

He concluded that a new type of ray was being emitted from the tube, capable of passing through the heavy paper covering and exciting the phosphorescent materials in the room. What made this extraordinary was that cathode rays, which scientists of the time understood, couldn’t travel more than a few inches through air—yet something was making that screen glow from several feet away.

Seven Weeks of Isolation

Röntgen didn’t leave his lab for weeks as he tried to investigate the source of the glow. He plunged into seven weeks of meticulously planned and executed experiments, systematically testing the properties of these mysterious rays.

During this intense period, he discovered that:

- The rays could penetrate various materials of different thicknesses

- They penetrate human flesh but not higher-density substances such as bone or lead

- They could expose photographic plates

- They traveled in straight lines

- They couldn’t be reflected or refracted like ordinary light

He named them X-rays because their nature was completely unknown—in mathematics, “X” represents an unknown variable.

The Famous Hand: Anna Bertha’s Skeletal Portrait

About six weeks after his discovery, Röntgen took a picture—a radiograph—using X-rays of his wife Anna Bertha’s hand. This image, taken on December 22, 1895, became one of the most famous photographs in scientific history.

The radiograph clearly showed the bones of her hand, her wedding ring, and the soft tissue as a shadow. When she saw her skeleton, Anna Bertha exclaimed “I have seen my death!”—a haunting reaction that captured both the wonder and unsettling nature of seeing inside the human body for the first time.

This wasn’t just a scientific curiosity—this was the first X-ray photograph of a part of the human body, marking the birth of medical radiology.

Going Public: The Scientific Bombshell

The Christmas Paper

Rontgens original paper, “Ueber eine neue Art von Strahlen” (On a New Kind of Rays), was published on December 28, 1895. The paper was remarkably concise—just 10 pages—but its impact was immediate and unprecedented.

Over Christmas, he wrote the article, which was accepted by the Proceedings of the Würzburg Physical-Medical Society. On New Year’s Day 1896, Röntgen personally mailed 90 reprints to physicists across Europe, ensuring rapid dissemination of his discovery.

Viral Before the Internet

On January 5, 1896, an Austrian newspaper reported his discovery of a new type of radiation, and the news exploded globally. Within a year roughly 1,000 publications appeared on the subject—an unprecedented rate of scientific adoption for the era.

In January 1896, he made his first public presentation before the Würzburg Physico-Medical Society, following his lecture with a demonstration: he made a plate of the hand of an attending anatomist, who proposed the new discovery be named “Rontgens Rays”.

Immediate Medical Revolution

From Laboratory to Hospital in Weeks

The medical community recognized the life-changing potential immediately:

- By February 1896, X-rays were finding their first clinical use in the US in Dartmouth, Massachusetts, when Edwin Brant Frost produced a plate of a patient’s Colles fracture

- In 1897, X-rays were first used on a military battlefield during the Balkan War to find bullets and broken bones inside patients

- In June 1896, only 6 months after Röntgen announced his discovery, X-rays were being used by battlefield physicians to locate bullets in wounded soldiers

Beyond Diagnosis: Therapeutic Applications

In January 1896, only a few days after the announcement of Rontgens work, a Chicago electrotherapist named Emil Grubbe irradiated a woman with recurrent cancer of the breast, marking the birth of radiation therapy. By year’s end, researchers were documenting the palliative effects of X-rays on various cancers and skin conditions.

The Stark Reality: The Hidden Dangers

Early Enthusiasm, Deadly Consequences

Initially, it was believed X-rays passed through flesh as harmlessly as light. This misconception led to widespread misuse with tragic consequences.

The Dark Side of Discovery:

- Within several years, researchers began to report cases of burns and skin damage after exposure to X-rays

- In 1904, Thomas Edison’s assistant, Clarence Dally, who had worked extensively with X-rays, died of skin cancer

- During the 1930s, 40s and 50s, many American shoe stores featured shoe-fitting fluoroscopes that used X-rays to enable customers to see the bones in their feet; it wasn’t until the 1950s that this practice was determined to be risky

Early experimenters, including physicians and scientists, suffered radiation burns, hair loss, cancer, and even death. The invisible nature of radiation made it particularly insidious—by the time symptoms appeared, irreversible damage had already occurred.

Modern Safety Standards

We now have a far better understanding of the risks associated with X-ray radiation and have developed protocols to greatly minimize unnecessary exposure. Today’s X-ray procedures use:

- Lead shielding to protect non-targeted areas

- Minimal exposure times calculated for necessary diagnostic quality

- ALARA principle (As Low As Reasonably Achievable)

- Digital technology requiring significantly less radiation than film

- Strict regulations governing equipment and procedures

Cultural Impact: X-Ray Mania

The public fascination with X-rays bordered on obsession:

Poems about X-rays appeared in popular journals, and the metaphorical use of the rays popped up in political cartoons, short stories, and advertising. The public imagination ran wild with possibilities both real and imagined.

Detectives touted the use of Röntgen devices in following unfaithful spouses, and lead underwear was manufactured to foil attempts at peeking with “X-ray glasses”. Studios opened to take “bone portraits,” further fueling public interest and imagination.

Scientific Legacy: Sparking a Revolution

Rontgens discovery triggered a cascade of breakthroughs:

Radioactivity Discovered

It led Henri Becquerel to look for connections with phosphorescence, leading to his discovery of spontaneous radioactivity in 1896. Marie and Pierre Curie were also taken by the X-ray work but upon hearing of Becquerel’s findings returned to isolating and identifying radioactive isotopes.

The Nobel Prize

Röntgen was awarded the first Nobel Prize in Physics in 1901, “in recognition of the extraordinary services he has rendered by the discovery of the remarkable rays subsequently named after him”. True to his character, he donated the prize money to his university.

Modern Applications: X-Rays Today

Medical Diagnostics

Today, X-ray technology is widely used in medicine, material analysis and devices such as airport security scanners. Modern applications include:

- Mammography for breast cancer screening

- Dental X-rays for oral health

- CT scans for detailed 3D imaging

- Fluoroscopy for real-time movement visualization

- Bone density scans for osteoporosis detection

Beyond Medicine

X-ray technology revolutionized:

- Airport security for luggage and passenger screening

- Industrial inspection for detecting flaws in materials

- Art conservation for examining paintings and artifacts

- Crystallography leading to DNA structure discovery

- Astronomy through X-ray telescopes studying cosmic phenomena

Book Your Journey Through Medical History with Mattese Lecque

Inspired by stories of scientific breakthroughs that changed humanity? At Mattese Lecque, we curate extraordinary travel experiences that bring history to life.

Explore Scientific Heritage Sites

Visit locations where history was made:

- Deutsches Röntgen-Museum in Remscheid, Germany (Rontgens birthplace)

- University of Würzburg where the discovery occurred

- Nobel Prize Museum in Stockholm showcasing the first Physics Prize

- Medical history museums worldwide featuring original X-ray equipment

Why Choose Mattese Lecque?

✓ Expert-curated itineraries connecting scientific landmarks ✓ Multilingual guides specializing in science history ✓ Exclusive access to museums and research facilities ✓ Educational experiences for students and professionals ✓ Customizable tours combining history, science, and culture

Ready to walk in the footsteps of scientific giants?

🌐 Website: www.matteselecque.com

Don’t just read about history—experience it. Book your scientific heritage tour with Mattese Lecque and discover the places where invisible rays became visible reality.

Conclusion: An Accident That Saved Millions

Wilhelm Rontgens accidental discovery on that November evening in 1895 wasn’t just a scientific milestone—it was a turning point in human history. From battlefield medicine to cancer treatment, from broken bone diagnosis to airport security, X-rays have become indispensable to modern life.

The story of X-rays reminds us that some of humanity’s greatest achievements come from curiosity, persistence, and the willingness to explore the unknown. Rontgens refusal to patent his discovery ensured that this life-saving technology could spread rapidly worldwide, embodying the highest ideals of scientific inquiry: knowledge shared freely for the benefit of all.

Today, over 3.6 billion diagnostic X-ray procedures are performed globally each year, each one a testament to that fateful November evening when mysterious rays revealed the invisible structure of reality itself.